Perhaps nowhere is the tension between our evolving nature and fixed perceptions more evident than in the workplace. Organizations, with their established hierarchies, role definitions, and cultural expectations, often function as powerful container that either nurtures or restricts the growth of our Dynamic Self.

However, it is not only the organizational structure that frames our fluid self but also our colleagues play a vital role in this. Our colleagues are a sample of our diverse social community whether from the local society or the global remote cultures. Each one carries an organizational acceptable mask but holds deep within the cultural expectations and heritage of his remote society. They have their own frames that they would like to impose on every colleague to save guard themselves.

BESTPRICE-ENDS-04FEB

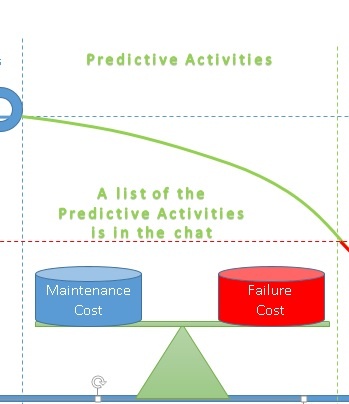

Threats from both of the organizational rigid structures and our colleagues can limit the space we allow our self to grow within. That’s a major setback for our human experience that is crowned by our dynamic self. You can read more about the importance of a dynamic self in this article: Embracing Your Dynamic Self: The Remarkable Power of Continuous Self-Awareness – P2

The Theatrical safeguard of our dynamic self

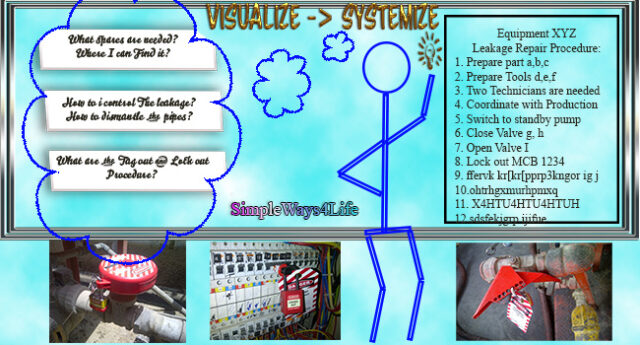

Sociologist Erving Goffman’s concept of “institutional selves” illuminates how organizational contexts shape our identities. In his seminal work “The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life,” Goffman describes how we develop specific personas for different institutional settings. Over time, these professional masks can become rigid constraints, particularly in static work environments.

He believes that when an individual comes in contact with other people, that individual will attempt to control or guide the impression that others might make of him by changing or fixing his or her setting, appearance, and manner. At the same time, the person whom the individual is interacting with is trying to form and obtain information about the individual. In social interaction, as in theatrical performance, there is a front region where the performers (individuals) are on stage in front of the audiences. This is where the positive aspect of the idea of self and desired impressions are highlighted. There is also a back region, where individuals can prepare for or set aside their role

BESTPRICE27JAN-01FEB

The Architecture of Constraint that restricts the growth of our Dynamic Self

Organizational psychologist Adam Grant identifies how static work environments create what he calls “perspective prisons”—limited ways of thinking that become normalized within an organization. “The culture of an organization,” Grant notes, “is shaped by the worst behavior the leader is willing to tolerate.” When leaders resist change, they implicitly encourage rigid self-definitions among team members which restricts the growth of our Dynamic Self.

Research by management scholars Herminia Ibarra and Jennifer Petriglieri reveals that “identity work“—the active construction and revision of one’s professional identity—requires psychological safety. Static organizations that penalize experimentation effectively shut down this essential developmental process.

Organizational Identity Traps

Several specific mechanisms in static work environments can lock down our dynamic potential:

Role Rigidity:

When organizations define roles narrowly and resist role evolution, professionals become trapped in outdated versions of themselves. As management theorist Peter Drucker observed, “The best way to predict the future is to create it.” Without the freedom to expand and redefine one’s role, professionals cannot create their future selves.

Status Quo Reinforcement:

Performance metrics that reward only established behaviors can have a stifling effect on personal evolution. By focusing solely on what has been proven to work in the past, these metrics discourage individuals from exploring new approaches or taking risks. This creates a culture where conformity is valued over innovation, and where the fear of deviating from established norms outweighs the potential benefits of discovering new and better ways of doing things.

As a result, individuals may feel constrained to stick with familiar patterns, even if they no longer serve them well. This can lead to stagnation, both personally and professionally, as people miss out on opportunities to learn, grow, and adapt to changing circumstances. By not rewarding exploration and experimentation, these metrics inadvertently reinforce a status quo that may not be optimal for long-term success or personal fulfillment. Encouraging exploration and innovation requires a shift in how performance is measured, one that values creativity and resilience alongside established achievements.

Feedback Deserts:

There is a problem that most professionals receive minimal constructive feedback—the very input needed to update self-perceptions. Static organizations often institutionalize feedback avoidance or work around. This creates what psychologist Susan David calls “emotional labor”—the suppression of authentic responses in favor of organizationally acceptable ones. Emotional labor refers to the process by which workers are expected to manage their feelings in accordance with organizationally defined rules and guidelines.

Cultural Embeddedness:

Anthropologist Claude Steele’s work on “stereotype threat” demonstrates how organizational cultures create implicit expectations about who can succeed and how. These cultural narratives become powerful shapers of self-perception, often constraining identity development along prescribed paths. Stereotype threat refers to the risk of confirming negative stereotypes about one’s racial, ethnic, gender, or cultural group. This phenomenon can lead to heightened stress, anxiety, and cognitive overload, which divert mental resources away from academic focus, performance, and relationship-building.

Ready to transform your mindset? Click and Get your copy > Now For Sale on Simpleways.life & Amazon

The Paradox of Professional Success

Paradoxically, professional success in static environments can accelerate this imprisonment of the Dynamic Self. As clinical psychologist Meg Jay notes in her work on adult development, “The most common regrets of professionals in their forties and beyond center not on failures but on the identities they failed to explore.” Meg Jay’s work does emphasize the importance of exploring and developing one’s identity during the twenties. She suggests that failing to invest in oneself during this decade can lead to regrets and an unfulfilling life. When we succeed within constrained definitions of self, we become increasingly invested in those limitations.

The danger lies in what sociologist Barry Schwartz calls “practical wisdom“—the ability to discern right action in specific contexts—becoming calcified into rigid doctrine. Schwartz advocates for practical wisdom as an essential quality that is being lost in our modern society, which increasingly relies on rules and incentives. Like a plant outgrowing its pot, our Dynamic Self requires expanding containers to flourish. When the organization refuses to provide these, professional growth becomes stunted or redirected toward less fulfilling paths.

As management expert once said, “In nature, growth occurs not from uniform addition, but from harmonious relationship with the environment.” Our professional selves require this same ecological attunement—environments that recognize and respond to our evolving capabilities, aspirations, and potential.

In Conclusion, the wisdom is in knowing what restricts the growth of our Dynamic Self

The Dynamic Self exists in constant tension with organizational environments that can either nurture or constrain its evolution. Through Goffman’s theatrical lens, we see how we adopt “institutional selves”—wearing professional masks that, while necessary for organizational functioning, can become rigid constraints over time.

The Architecture of Constraint reveals itself through workplace structures that create “perspective prisons,” limiting our potential growth. These constraints manifest in Organizational Identity Traps including role rigidity, status quo reinforcement, feedback deserts, and cultural embeddedness—all mechanisms that lock our identity into outdated versions of ourselves.

Perhaps most insidious is the Paradox of Professional Success, where achievement within constrained definitions of self increases our investment in those very limitations. Our success can accelerate our imprisonment when we identify too strongly with a particular professional persona.

In the coming article we shall explore how Safeguarding our Dynamic Self requires strategic approaches: cultivating psychological safety as foundation, designing appropriate learning edges, creating identity workspaces, balancing structure with flexibility, and practicing conscious role crafting.

If you feel you need help with any of these ideas we discussed, request a Management Consultancy or Coaching Services From our Store